Call for a new data governance structure

A summary of the new book chapter for the DFC Book Collection Education Data Futures.

A huge amount and range of education data is routinely collected in UK state schools (Persson, 2020). These data can be collected and processed at schools for a variety of purposes. Sometimes, schools are collecting these data under their obligation to the Department for Education (DfE); other times, they need to process children’s data as part of teaching, assessment, administrative and safeguarding (DFC, 2021b). Finally, schools are increasingly contracting external EdTech companies to process children’s data to enhance their learning and education opportunities.

While schools are expected to be the primary duty bearers of children’s best interests, their duties are compounded by the complexity of legislation in the education sector and the extreme challenge of carrying out compliance validation. To shed lights upon this challeging situation, the Digital Future Commissions and 5Rights Foundations called for a timely peer-reviewed essay collection, namely Education Data Futures, which was launched on 21 November 2022.

Researchers from the EWADA project contributed our thoughts of a technical alternative to the current learning data management and governance paradigm for UK state schools. Our proposal is based on the new wave of decentralised paradigms for data sharing and ownership. This decentralised data governance is anticipated to expand individual data subjects’ ability to access data and establish data autonomy. A data trust is one such data governance model, which provides a promising response to schools’ need for an independent and trustworthy body of experts who can make critical decisions about who has access to data and under what conditions.

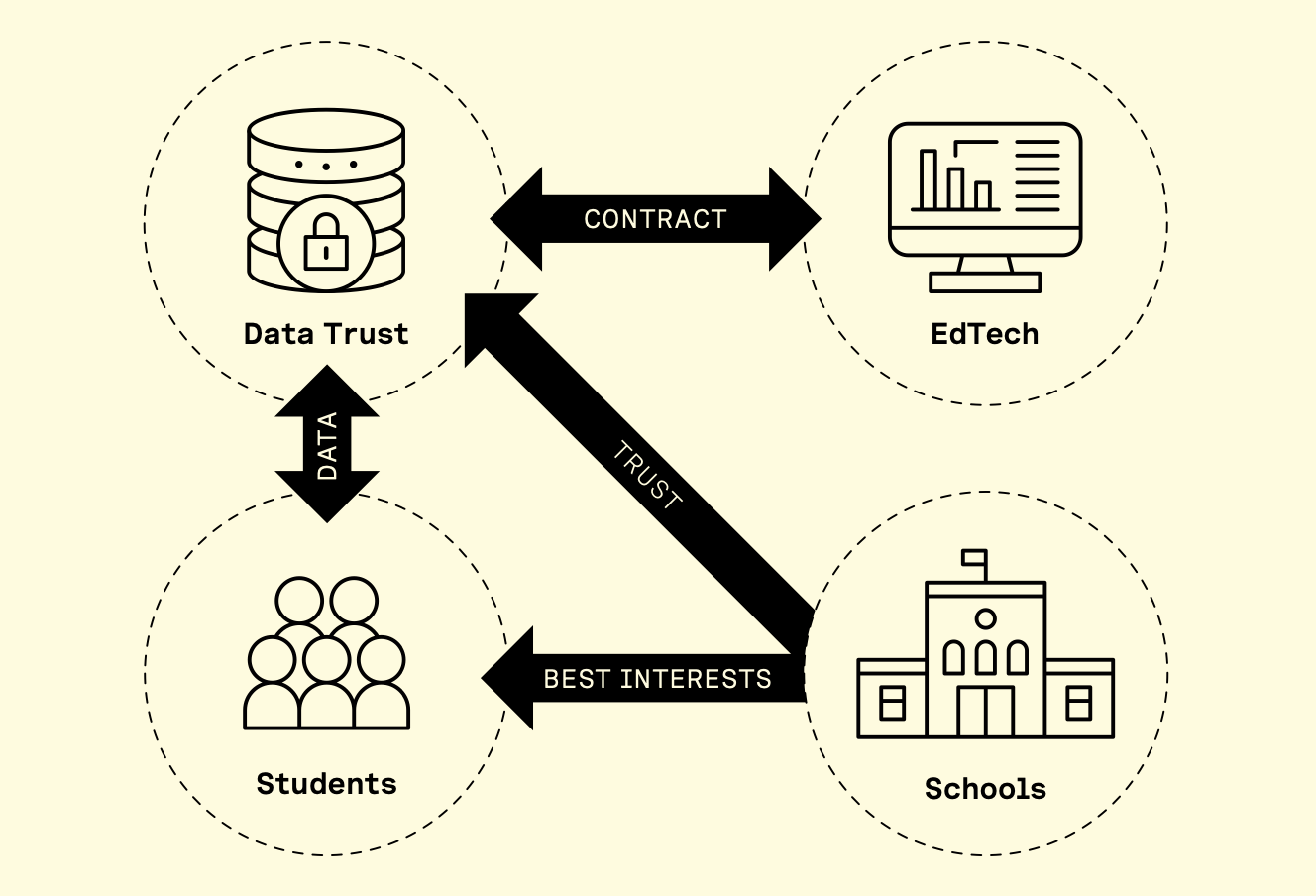

A data trust as ‘a legal structure that provides independent stewardship of data’, including deciding who has access to data, under what conditions and to whose benefit (Open Data Institute, 2019). It is different from other data governance structures because it represents ‘a legal relationship where a trustee stewards data rights in the sole interests of a beneficiary or a group of beneficiaries’ (van Geuns & Brandusescu, 2020). Instead of taking a grassroots governance model (such as a data commons), the trustees can be the decision-makers regarding who has access, under what conditions and to whose benefit, and they take on a legally binding responsibility for data stewardship (Open Data Institute, 2019).

It has been exciting to see some practical developments of data trusts recently, built on extensive theoretical landscaping. However, developing data trusts is a complex task and requires a strong commitment from data holders and the users’ community. Furthermore, existing legal frameworks are not necessarily ready to support all the data stewardship and legal binding responsibilities designed for a data trust. The essay runs through a case study about personalised learning at school to demonstrate what a data trust model may provide.

As shown in the figure below, a data trust can act as an intermediary for schools, making decisions about what education data can be accessed by a third party, investigating the purposes of data access, and assessing how they may be aligned with students’ best interests. It provides a promising direction for mitigating the challenges that schools face regarding data safeguarding and compliance checking.

However, developing such a data trust is not without challenges. The essay concludes by discussing open social, legal and technological challenges to be considered, calling for a pilot model of data trusts in the educational technology (EdTech) sector, for which the technologies of the EWADA project could notable contributions to.

Please follow the link for further reading about the essay pdf and the essay collection.